History of Coffee

In this article we will review the history of coffee, from its ancient discovery to the present day, and its fascinating journey through time.

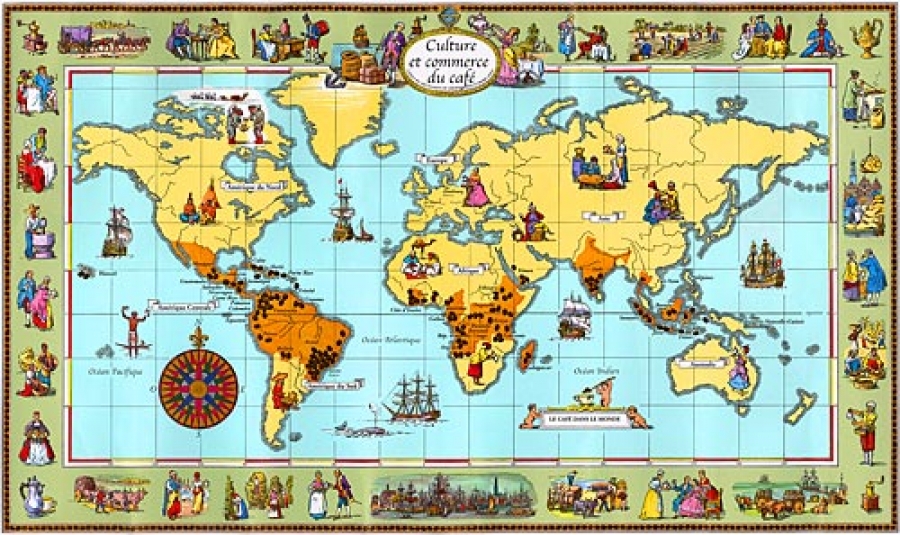

Origin and diffusion of coffee around the world

It was in the Orient that, since the earliest of times, coffee became popular at all social levels. In several ancient Arab legends, stories are told about this mysterious beverage – black and bitter – with unknown stimulant properties. However, it was only three centuries ago that coffee reached the West. While its discovery and the practice of roasting beans happened by chance, the same thing cannot be said about its name, which unmistakably comes from the plant on which it grows, indigenous of an Ethiopian region called Kaffa.

Coffee began its journey from here, reaching Yemen and, a short time later, spreading to Arabia and Egypt, where it became part of the daily lives of commoners and sovereigns alike.

Trade contacts then intensified between East and West in the sixteenth century, and the arrival of coffee was greeted enthusiastically in the Old and New Worlds. However, it took nearly 200 years to transform this enthusiasm into a strong and well-established trade. In fact, it was not until 1690 that the Arab monopoly on world coffee production came to an end and a new player – the Dutch tradesmen – came onto the scene.

Until then the secret of the precious plant was jealously guarded by the Yemenites. It began to discover new horizons when Baba Budan, an Indian on a pilgrimage to Mecca, introduced the mysterious beverage to Misore, a Dutch colony in India. All this took place through an intriguing ruse: Baba Budan hid some coffee beans in his robes. From there, things moved quickly. The Yemenites lost their exclusive trade, and the privilege of growing coffee was shared with the Dutch who, led by Nikolas Witten, landed on the coasts of Moka, in Yemen and seized a prized coffee plant. Though it was just one plant, this specimen made it possible to achieve an extraordinary objective: generating all the plantations that can be seen around the world even today.

The Dutch holdings in the Indies, and then the greenhouses of the botanical gardens in Amsterdam, would become home to one of the most beloved plants in the world, opening up the path to large-scale development in Batavia, the island of Java and, subsequently, the East Indies, Ceylon and Surinam.

The Dutch ships of the East India Companies circumnavigated the Cape of Good Hope and brought their precious cargo to the port of Rotterdam. From here, in just a few years, the great European coffee market developed. It was around the year 1700 that the Mediterranean Sea, the “crossroads” of different worlds, marked the route that brought coffee to Europe.

From the Orient, this precious beverage then reached Venice, Naples, Marseille, Amsterdam, Hamburg and London, and became regularly consumed across the Old Continent.

For the coffee plant, the year 1723 is a historic date: this is the year the plant was brought to Central and South America, as a result of colonisation. Everything began when Frenchman Gabriel de Clieu, a captain and lieutenant of the overseas infantry, went to Paris and asked the court gardeners at the King’s Royal Gardens in Versailles to give him one of the four coffee plants grown there to transplant it in Martinique. In the month of May, the captain set sail from Nantes heading towards the Antilles, and was forced to watch over the plant day and night, as its survival was threatened by the endless adventures encountered on this journey. Upon arrival, Gabriel de Clieu planted it – it was only a few centimetres high at that point – and twenty months later he had an abundant harvest.

The beans were distributed to religious buildings and to the locals, who had quickly perceived the enormous economic value of this kind of production. Within just three years, the island was literally covered by thousands of coffee plants, which were brought not only to Guadalupe and Santo Domingo, but also to the other French colonies: Guyana, the Antilles, Costa Rica and even the island of Bourbon, later renamed Réunion.

The new crop’s success in Martinique was also due to the eruption of the volcano on the island, which destroyed the cocoa plantations. As a result, they were replaced with coffee plants. The harvest from these territories allowed France to maintain its leadership on European markets until the fatal block imposed by Napoleon, when other producers naturally took advantage of the situation. Also in 1723 the Dutch and French successfully exported the plant, the former to the overseas colony of Java and the latter to the island of Martinique.

Nevertheless, Brazil – which is currently the world’s largest producer – remains the true earthly paradise of coffee. Its arrival in Brazil was not simple and, indeed, the advent of the black beverage was quite eventful. The year was 1727, and the credit goes to the brilliant Brazilian lieutenant Francisco de Mello Palheta. The occasion was the diplomatic encounter with the governor of Cayenne, Claude de Guillonet (Lord d’Orvilliers), to settle certain disputes over the border with Guyana.

During the lunch organised by the governor, coffee and liqueurs were served, and Palheta asked his host for a few beans to plant in his garden. Lord d’Orvilliers politely but decidedly refused, as he had received strict orders from his government not to allow even one bean to be taken. After lunch, the dashing Brazilian lieutenant took the governor’s wife aside for a tête-à-tête. As they walked past a coffee plant laden with red fruit, the noblewoman, charmed by the Brazilian’s attentions, picked a few cherries and slipped them in the officer’s pocket, adding: “Take them. My husband has been ordered not to give them to anyone, but I’m free to offer them to anyone I like”.

In his book Vida Maravilhosa e Burlesca do Cafe, Teixera de Oliveira confirms that Palheta’s real mission in Cayenne was to obtain a few beans to cultivate on his land and not to settle border problems. This ploy is also proven by several documents found in Brazilian archives: “Gain access to some garden with coffee plants and, using the pretext of wanting to taste the fruit, try to obtain a few beans without being seen.” In just a few decades, these crops extended across the State of Paranà. Despite the immensity of the territory and the resistance posed by the French and Dutch, who held the monopoly at the time, the Brazilians’ obstinacy was rewarded, and even though there have been highs and lows, Brazil is still the biggest coffee-producer in the world.

The first plantations in the north of the country, which were started in 1727, had to face rather unfavourable climatic conditions. Therefore, the decision was made to move the plantations first to Rio de Janeiro and, lastly, during the first half of the nineteenth century, to the States of São Paolo and Minas. These were ideal environments for new plantations, which rapidly became the most important economic resource of the country. Despite its African origins, coffee enjoyed its maximum expansion in Central and South America. The return to its land of origin is also quite recent. It was not until the end of World War I that the legendary beverage reached the African continent again, through the British who gave new impetus to cultivation in Central Africa, thereby restoring to those areas what had been exported around the world.

The history of coffee in Italy

The guilds of the great merchants, who already specialised in trading exotic spices, crossed the Mediterranean with their sailing ships and, during the second half of the sixteenth century, they introduced these legendary beans to the leading ports of Europe. In 1570, Venice, the true emporium of the Orient, became the first city to import coffee, which was introduced at the same time as tobacco. Credit for the coffee arrival on the scene goes to Prospero Alpini, a well-known physician and botanist. During a long stay in Egypt, he noticed that the local populations brewed a dark beverage made from seeds which had been scorched, ground and boiled. In just a few years, the beverage became very popular among the Venetians and the business it generated gradually increased. In 1683, the first “coffee shop” was opened in Venice under the arcade of the Procuratie in St. Mark’s Square.

Very soon the city’s small squares were thriving with more and more shops to the point that the Venetian authorities tried to stop the new phenomenon. The introduction of coffee was also opposed by several prelates of the Church, who asked Pope Clement VIII to ban what they defined “the devil’s beverage” – but to no avail. According to historical accounts, after tasting a cup of coffee the Pope himself exclaimed, “This beverage is so delicious that it would be a shame to allow only non-believers to drink it. We shall vanquish Satan by giving it our blessing to make it a ‘Christian’ drink. Indeed, this marked the beginning of the golden age of coffee, which became an increasingly popular drink among Italians.

Now that it had lost its exclusive image as a medicinal drink, the legendary beverage was consumed anytime and anywhere, in elegant shops and rustic popular cafes. In social circles, coffee was the perfect accompaniment to both lofty and more common discussions, becoming an expression of the art and culture of the Italy of the future. This euphoria also influenced the great Venetian writer, Carlo Goldoni, who wrote The Coffee House and Pietro Verri, who in 1764 founded the weekly philosophical-literary journal with the eloquent title Il Caffè. Goldoni’s work is also set in one of the first Italian “coffee shops”: the Caffè Florian in Venice. This confirmed the success of a new fashion that, as well as the rest of Europe, quickly conquered other marvellous Italian cities.

Some of the most important cafés from both a historic and artistic point of view are the Mulassano, San Carlo and Caffè Torino in Turin, Pedrocchi in Padua, and the Caffè Greco in Rome. Public speakers and disgruntled politicians would speak here against the government, literary people would harshly criticise their colleagues and journalists would cover the stories. Anyone could take part in the conversation, and even the waiters – tray in hand – would politely interrupt customers to express their opinions.

Even today, art and culture come together in these cafés, the symbols and historic temples of Italian tradition. They were places where artists, politicians and men of letters from around the world would meet in elegant and sumptuously decorated rooms to sip a good cup of coffee.